Kristi here. If you live in the United States and you’re reading this article it means either A) you’ve already finished your taxes or B) you’re avoiding doing your taxes by perusing the internet. If the latter I suggest you hop to it because Tax Day is right around the corner.

“The only things certain in life are death and taxes.” – Benjamin Franklin

How true, how true. Taxes are a way of life if you want to have a funded government. During the Regency, with the American Revolution having just wrapped up and the Napoleonic Wars raging, not to mention a Prince Regent with an eye for expensive decor, the English government taxed the citizens in every way it could think of. Newspapers, soap, tea, pins, sugar, coffee, even horses and dogs were taxed. By the time the Regency rolled around the English government had gotten very good at taxing people in unique ways.

The Window Tax

Probably the most infamous of the taxes was the window tax. It was doubly bad because there was also a Glass Excise tax. So you got taxed when you bought the glass for the window and then taxed for having the window.

Probably the most infamous of the taxes was the window tax. It was doubly bad because there was also a Glass Excise tax. So you got taxed when you bought the glass for the window and then taxed for having the window.

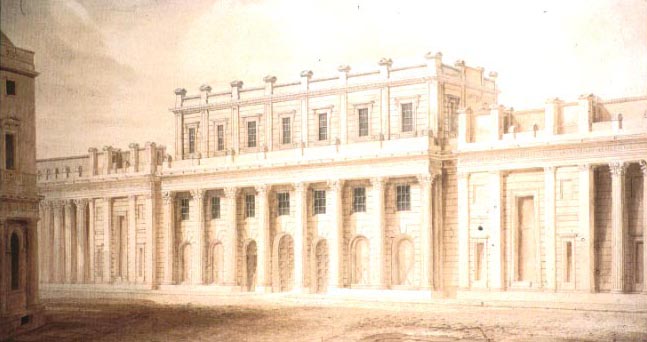

Any portal that allowed you to see outside of the house – even a small ventilation hole – counted towards a home’s total number of windows. Homes were classed into three groups: less than 10 windows, 10-20 windows, and more than 20 windows. The rates were occasionally raised, coming to their peak during the Regency, before slowly decreasing until the tax was eradicated altogether in 1937.

While some people, particularly poor people, did brick up certain windows to avoid the tax, false windows were also a popular architecture feature. This was awfully convenient if you did want to brick up a window because it kept it from looking out of place.

The Servant Tax

Next time you’re reading (or writing!) a Regency novel, pay attention to the number of people running around performing services for all the characters. All of them drew a tax from their employers. Footmen, butlers, valets, game-keepers, grooms, and gardeners all added together to make money to fund wars on the American and French fronts. The scale was as difficult to figure out as their money.

Next time you’re reading (or writing!) a Regency novel, pay attention to the number of people running around performing services for all the characters. All of them drew a tax from their employers. Footmen, butlers, valets, game-keepers, grooms, and gardeners all added together to make money to fund wars on the American and French fronts. The scale was as difficult to figure out as their money.

Families were charged different rates than bachelors. Eventually a sliding scale, based on the number of servants you employed, was applied to the rates.

Originally the law applied only to male servants working in homes or on estates. By the time Prinny came to power, women servants, waiters, book-keepers, clerks, stewards, and even factory workers and farm laborers were being taxed. The rates had also been risen to their highest point in history, making the sheer effort of making a living and running a household an expensive endeavor. While things did get better after 1823, the tax was not entirely repealed until 1889.

The Church Tax

Yes, the Church of England was also in the game of raising funds. At the time the church was responsible for much more than religious education, fellowship, and Godly worship. They also cared for the roads, the poor, and upkeep of certain public buildings – including the place of worship.

This was separate from the tithes expected from farmers and craftsmen which paid the living for the clergy. Also, while not a requirement, it was expected that people pay pew rental fees to the church to secure their seats for worship services. One would also have to tip the person who opened your pew box for you to sit down.

All of this taxation served to make the poor poorer and the rich a little irritated. The poorest of people lived in houses without ventilation and didn’t wash because of the tax on soap. This made them sick and unable to care for themselves, in which case they had to rely on the church which meant the church had to collect more in taxes as well which led the rich to go to great lengths to drive the poor to another district. What a vicious circle.

Sadly, things haven’t changed much. Between income tax, property tax, sales tax, ad valorem tax, and other things like estate and capital gains taxes, just about everything we touch is taxed as well. I guess Ecclesiastes is right… there’s nothing new under the sun.

Sources:

What Jane Austen Ate and Charles Dickens Knew

Godly Mayfair

English Historical Documents 1660-1714

Regency Redingote

Regency Redingote

Originally posted 2012-04-16 10:00:00.

included a feathered headdress and hoopskirts. This was known as her come out. An average debutante might attend 50 balls, 60 parties, 30 dinners, and 25 breakfasts over the course of a season.

included a feathered headdress and hoopskirts. This was known as her come out. An average debutante might attend 50 balls, 60 parties, 30 dinners, and 25 breakfasts over the course of a season. considered a failure. The season ended officially on August 12, when Parliament adjourned, after which everyone retreated to their country estates.

considered a failure. The season ended officially on August 12, when Parliament adjourned, after which everyone retreated to their country estates.