Regency Reflections is excited to welcome Regan Walker. Over the next three days we will be sharing a paper Regan wrote entitled “God in the Regency”. This three part series will give you a terrific overview of the religious environment and shifts in the Regency period.

Part One posted yesterday. Read it here.

Regency England (and the 19th Century)

Against this background, we emerge into Regency England (1811-1820, extending to 1837 if we consider the larger “Regency Era,” ending when Queen Victoria succeeded William IV). During this period, the religious landscape consisted of the Anglican Church of England, which occupied the predominant ground (though the Evangelicals continued to dominate the Church in the first half of the 19th century), and those considered “Dissenters,” a general term that included non-conformist Protestants, Presbyterians (identified with the Scots), Baptists, Jews, Roman Catholics and Quakers. The Protestants moved toward the Methodist and Evangelical perspective, and a personal conversion experience. The Roman Catholics, governed by the Pope in Rome, though discriminated against, were too strong to be suppressed and persisted, eventually regaining the ability to become Members of Parliament and hold public office with The Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829. (Ironically, the Prince Regent opposed Catholic Emancipation even though Maria Fitzherbert, a twice-widowed Roman Catholic, was arguably the love of his life.)

There were many incentives to be a part of the Church of England because it was government controlled and sponsored. Only Anglicans could attend Oxford or receive degrees from Cambridge. Except for the Jews and Quakers (the latter which received freedom of worship in 1813), all marriages and baptisms had to take place in an Anglican church. All citizens, no matter their faith, paid taxes to maintain the parish churches, and non-Anglicans were prevented from taking many government and military posts.

According to Henry Wakeman in An Introduction to the History of the Church of England, by the time George III died in 1820, despite all that occurred in the 18th century with the Evangelical and Methodist revivals, with a few exceptions (some discussed in this article), the Church of England was not materially different than it was when George III came to the throne in 1760.

The bishops were still amiable scholars who lived in dignified ease apart from their clergy, attended the king’s levee regularly, voted steadily in Parliament for the party of the minister who had appointed them, entertained the country gentry when Parliament was not sitting, wrote learned books on points of classical scholarship, and occasionally were seen driving in state through the muddy country roads on their way to the chief towns of their dioceses to hold a confirmation. Of spiritual leadership they had but little idea. (Wakeman at 457)

Jane Austen wrote about the world of the Anglican clergy. Her father was the Reverend George Austen, a pastor who encouraged his daughter in her love of reading and writing. (In addition to her novels, Jane Austen composed evening prayers for her father’s services.) She also had other relatives, including two of her brothers, who were among the Anglican clergy. It was a culture in which faith often influenced one’s livelihood. Some of Austen’s characters (i.e., Edward Ferrars and Edmund Bertram) were clergy in need of parsonages. It was an acceptable occupation for a younger son. Large landowners and peers owned many of the church appointments and could appoint the local clergyman.

Of the Anglican clergy, Wakeman said,

The bulk of the English clergy then as ever were educated, refined, generous, God-fearing men, who lived lives of simple piety and plain duty, respected by their people for the friendly help and wise counsel and open purse which were ever at the disposal of the poor.

A few of them hunted, shot, fished and drank or gambled during the week like their friends in the army or at the bar, and mumbled through a perfunctory service in church on Sundays unterrified by the thought of archdeacon or bishop. Some of them, where there was no residence in the parish, lived an idle and often vicious life at a neighbouring town, and only visited their parishes when they rode over on Sundays to conduct the necessary services. (Wakeman at 459)

[With few exceptions] the clergy held and taught a negative and cold Protestantism deadening to the imagination, studiously repressive to the emotions, and based on principles which found little sanction either in reason or in history. The laity willingly accepted it, as it made so little demand upon their conscience, so little claim upon their life. (Wakeman at 461)

Wakeman recognized the indifference of the Church of England to the “tearing away” of the followers of Whitefield and Wesley:

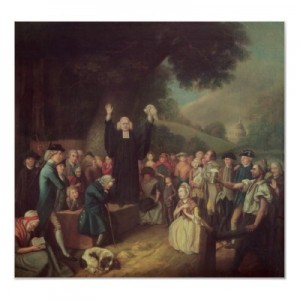

An earnest revival of personal religion had deeply affected some sections of English society. Yet…the Church of England reared her impassive front…sublime in her apathy, unchanged and apparently unchangeable….

Unlike some Anglicans, who may have attended church only out of duty or habit, Jane Austen was more than a nominal church member. From the prayers she wrote, she seems to have been a devout believer who accepted the Anglican faith as it was, though she disliked hypocrisy and that may be reflected in some of her clergyman characters. She also had views on the Evangelicals. In a letter to her sister Cassandra, written on January 24, 1809, she admitted, “I do not like the Evangelicals.” Like many Anglicans, she likely felt faith was to be unemotional and demonstrated in observances of certain services, prayers and moral teachings. The demonstrative preaching and strong message of the Evangelicals, particularly their enthusiasm and fervor, might not appeal to a girl raised in an Anglican minister’s home. Then, too, she had experience with certain Evangelicals, notably her cousin Edward Cooper, who she observed in a letter to her sister, wrote “cruel letters of comfort.” (It is very human, is it not, to judge a movement by the few persons we may know within it?) However, as she grew older, there is some indication of a softening in her thinking. On November 18, 1814, Austen wrote a letter to her niece, Fanny Knight, in which she said, “I am by no means convinced that we ought not all to be Evangelicals, & am at least persuaded that they who are so from Reason & Feeling, must be happiest & safest.”

Perhaps as Austen viewed the decadence of the Regency period (particularly the social life in London), the indulgences of her monarch, and the lackluster faith of some who adhered to the Church of England out of habit, she found value in the sincerity of those who espoused a more evangelical message. It was, after all, the Evangelicals led by William Wilberforce, allied with the Quakers that became the champions of the anti-slavery movement, resulting in the Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1807. Among Jane Austen’s favorite writers were those who were passionately anti-slavery, such as William Cowper, Doctor Johnson and Thomas Clarkson. One of her naval brothers, Frank, after a visit to Antigua in 1806, wrote home condemning slavery.

Austen was critical of the Prince Regent, understandably so. Unlike his parents, George III and Queen Charlotte, the Prince Regent lived a decadent life, indulging in his personal pleasure devoid of any evidence of a strong faith, or indeed any faith at all, though he was nominally the head of the Church of England. As a result of the tax burden from the wars in France and the Prince’s opulent lifestyle that was crushing the poor and working classes, the resentment for the Prince grew more strident as time went on. Jane Austen disliked him intensely, principally because of his treatment of his wife, Princess Caroline of Brunswick (as seen in her letter to Martha Lloyd of February 16, 1813). She was not pleased when it was “suggested” she dedicate her novel Emma to him in 1816, though she did so for marketing reasons.

In at least some parts of the Church of England during the Regency, spiritual change was afoot continuing from the movements in the 18th century. In such places, the Church of England looked more like the Protestant Evangelicals. For example, Charles Simeon, rector of Trinity Church, Cambridge for 54 years (1782-1836), and a member of the Clapham group, was a great Bible expositor, who taught a risen Savior and salvation through grace, sounding very much like Wesley and Whitefield decades earlier. That was no mean feat given the opposition he faced in Cambridge. The universities were bastions of the established Church of England and seedbeds of rationalism, neither of which made them sympathetic to a rector of strong religious fervor.

Anglicans distinguished between the “High Church” and the “Low Church.” The High Church or “Orthodox” church, associated with the Tories, was content with the state’s involvement in religious matters and associated itself with the court and courtiers and emphasized the rituals of the church and the Common Book of Prayer. The Low Church, associated with the Whigs and with Cambridge, and before they broke off, with the Methodists, presented a middle ground where faith was tolerant, rational and low-key. To the Low Church, the Bible was all-important and the Book of Common Prayer considered merely a human invention that could be adapted and changed. To those in the Anglican High Church, Low Church members, like Charles Simeon, were merely “Dissenters in disguise.” The Evangelicals were opposed by both the High and Low Church of the Anglicans, particularly because of their enthusiasm (their fervor raised the specter of the troubles in France). Because of their strong stance on moral issues, the Evangelicals of that day were also viewed by some as troublemakers who didn’t want anyone to have any fun. Notwithstanding such views, there were those in the aristocracy, including the William Cavendish, the 6th Duke of Devonshire, who became Evangelicals though they never left the Anglican church.

One effect of the Methodist and Evangelical influences, begun in the 18th century and continued in the Regency, was the growth in foreign missions, as Christians went to other parts of the world to spread the “good news.” There were many English men and women whose newfound faith compelled them to accept the challenge for the cause of the gospel. Missionary societies, initially viewed with disfavor by the established church, gained in prominence in the 19th century.

Charles Simeon was one of those clergymen in the Church of England who was interested in missions and spreading the Bible’s message around the world. He took a special interest in India and sent his former assistants as chaplains with the British East India Company. Henry Martyn may be the most famous of those assistants. He served in India and Persia from 1806 until his death in 1812, and during those few years, translated the New Testament into Persian, Urdu and Judaeo-Persic. He influenced young people for generations to go to the mission field and is remembered as saying, “The spirit of Christ is the spirit of missions. The nearer we get to Him, the more intensely missionary we become.” Such a faith was not one of ritual or habit but a faith that moved one to action and personal sacrifice.

God in the Regency will continue with part 3 tomorrow.

After years of practicing law in both the private sector and government, and traveling to over 40 countries, Regan has returned to her love of telling stories. She writes mainlineRegency romances, her first is Racing With The Wind, set in London and Paris in1816, and features spies and intrigue as well as a smart, independent heroine and a handsome British lord–lots of adventure as well as love! It’s the first in her Agents of the Crown trilogy. For more, see her website: http://www.reganwalkerauthor.

After years of practicing law in both the private sector and government, and traveling to over 40 countries, Regan has returned to her love of telling stories. She writes mainlineRegency romances, her first is Racing With The Wind, set in London and Paris in1816, and features spies and intrigue as well as a smart, independent heroine and a handsome British lord–lots of adventure as well as love! It’s the first in her Agents of the Crown trilogy. For more, see her website: http://www.reganwalkerauthor.

Originally posted 2012-10-25 10:00:00.

Comments are closed.