Trial by Combat

Or the Changing Face of Justice

“Those woods are mine and mine alone for hunting.”

“I am afraid, sir, that you are mistaken. Thos woods belong to my family and have been for six hundred years.”

“The deed to the land says otherwise.”

“My sword says more otherwise than the deed.”

“En guard!”

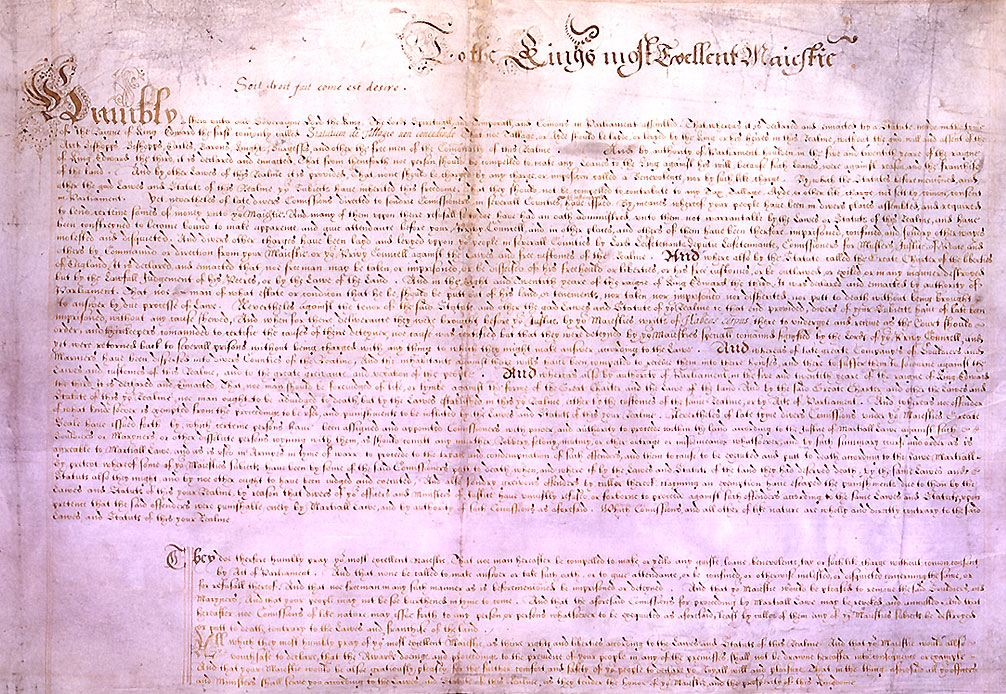

With clashing swords and combat to first blood or death, trial by combat, whether criminal or civil, was not an uncommon way to settle disputes in England in the Middle Ages. In fact, the issue arose in 1818 when someone demanded to settle a dispute in such a manner.

“Are you saying that is still on the books?” One can hear the authorities exclaim. “But we are civilized now. We have a different system.”

Yes, indeed, it was still on the books, though hadn’t been used for hundreds of years.

By the Regency, England’s courts had evolved from the days of trial by ordeal or combat or simple pronouncements from on high. They had become a complex and loosely jointed system of magistrates, justices of the peace, and circuit judges for the assizes.

How the system evolved from the days of Anglo-Saxon rule until the Regency is a complex system on which entire books have been written. This is a brief description of the duties of the men who handled around ninety-five per cent of England’s criminal cases during our time period. It changed again in 1830, and then again in 1971, and we don’t need to fret about those because this is its own era.

Who were justices of the peace and magistrates? They were usually gentlemen who sat in the various offices in London, hearing criminal trials brought to them from various sources. Coroners for murder, for example. Bow Street is the most famous of these offices, and possibly the most famous of the Bow Street magistrates is Sir John Fielding, brother to the eighteenth century author and also a Bow Street magistrate.

Fielding, Sir John, was called the Blind Beak of Bow Street. A “beak” in street cant, was a respected man. Sir John was blinded serving in the royal Navy, but legend has it that he recognized the voices of 3,000 criminals.

Outside of London, we had justices of the peace. These were gentlemen, but not peers. If a peer was a justice of the peace before gaining a peerage, he could keep the post, and peers did not take on the role. JPs performed the same duties of hearing cases as did magistrates. They were simply outside of London. Both sent serious criminal cases up the chain to higher judges.

On a side note here, neither magistrates nor justices of the peace could perform weddings at this time. That fell solely under the jurisdiction of the Church of England.

Outside of London, circuit judges traveled around the country and held trials at the assizes. Assizes occurred twice a year. That meant an innocent man accused of murder could languish in prison for up to six months until the next meeting of the assizes.

Inside London, serious crimes such as murder were heard by the Court of the King’s Bench.

Sadly, corruption, taking of bribes, and other forms of misconduct by judges was not uncommon. In some eras, though I haven’t found much evidence of it during the Regency, judges were removed and even sentenced to death for corrupt practices.

Regardless of these slips into sin, a trial before a judge and jury proved far more effective than trial by combat or ordeal.

Originally posted 2012-11-30 10:00:00.