Regency Reflections is excited to welcome Regan Walker. Over the next three days we will be sharing a paper Regan wrote entitled “God in the Regency”. This three part series will give you a terrific overview of the religious environment and shifts in the Regency period.

Other factors should be considered because of how they influenced people’s view of God during this time. New ideas in politics, philosophy, science and art all vied for people’s attention. Two in particular, the scientific discoveries of the time and the Industrial Revolution, may have had dramatic effect on man’s view of his faith during the Regency.

In 1781, while investigating what he and others believed to be a comet, William Herschel, an astronomer, discovered a new planet he named “George’s star,” after King George III. (In 1850, after Herschel’s death, the name would be changed to Uranus.) This was the first planet discovered since ancient times. In 1816, Herschel was knighted, and in 1821 he became President of the Astronomical Society for his achievements. Herschel, a devout Christian, strongly believed that God’s universe was characterized by order and planning. His discovery of that order led him to conclude, “[T]he undevout astronomer must be mad.”

Herschel’s discoveries caused his fellow scientists and theologians to reconsider their prior views of God and the possibility there were other creations in the universe. Not all views expressed were those of believers in God; however, one who was is illustrative of the prevailing attitude. Thomas Dick, a Scottish minister and science teacher, in his book The Sidereal Heavens, published in 1840, said of Herschel’s discovery,

To consider creation, therefore, in all its departments, as extending throughout regions of space illimitable to mortal view, and filled with intelligent existence, is nothing more than what comports with the idea of HIM who inhabiteth immensity, and whose perfections are boundless and past finding out.

Though he wrote this after the Regency, Dick’s statement is indicative of the view during the early 19th-century in which science was dominated by clergymen-scientists, men dedicated to their scientific work but still committed to their faith in God. Scientific discoveries were seen as entirely consistent with a belief in a Creator. Geologist William Buckland, mathematician Baden Powell and polymath William Whewell found little conflict in their roles as clergymen and men of science.

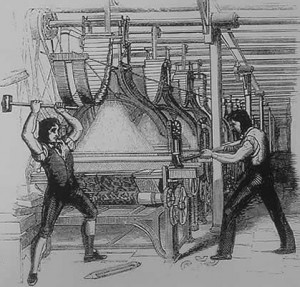

The Industrial Revolution transformed English society during the 18th and 19th centuries and would certainly cause people to question the established order of things, including the church. During the 18th century, England’s population nearly doubled. The industry most important in the rise of England as an industrial nation was cotton textiles. A series of inventions in the 18th century led to machines that could and did replace human laborers, and the use of new, mineral based materials that replaced those based on animal and vegetable material. The effect of machines replacing workers, particularly in the textile industry, was keenly felt in some parts of England.

During the period 1811-1816, a group called “the Luddites” reacted by smashing thousands of machines developed for use in the textile industries in Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire; thus the Midlands became the center of much unrest. The poor, crippled by bad harvests and taxes and resentful at having no vote, rose up. At times, the clergy would even become involved. For example Hugh Wolstenholme, curate of Pentrich in Derbyshire, took a stand on the side of his parishioners and was critical of the government in the Rebellion of 1817. For his role, he had to flee to America. Interestingly, he attended Trinity College Cambridge when Charles Simeon was the rector.

As England changed from an agricultural to an industrial economy during the 19th century, the lives of the working class were disrupted and many people relocated from the countryside to the towns. In 1801, at the time of the first census, only about 20% of the population lived in towns. By 1851, the figure had risen to over 50%. New social relationships emerged with the growing working and middle classes. During this time of upheaval and relocation, which began in the Regency, though some individuals, like Charles Simeon, exercised great spiritual influence, the Church as a whole would fail to grapple with the problems that resulted from the huge surge in population and the growth of industrial towns. Still, perhaps both the problems and the movement of people to the towns, where they might have heard the message of the great preachers of the day, spurred them to examine their faith. One can only hope.

Selected Sources and Books/Articles of Interest:

Several of the resources listed below can be clicked on to take you to them.

All Things Austen, An Encyclopedia of Austen’s World, Vols. I & II (articles on the Clergy and Religion) by Kirstin Olsen

Selina, Countess of Huntingdon by Faith Cook

The Bachelor Duke, 6th Duke of Devonshire 1790-1858 by James Lees-Milne

An Introduction to the History of the Church in England by Henry Offley Wakeman (3rd edition, 1897 on Google Books)

A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Higher and Middle classes in This Country Contrasted with Real Christianity, by William Wilberforce, 1798

Religious Upheaval During 17th Century England by Katherine Pym

The Clapham Sect by O. Hardman

Life in the 19th Century by Tim Lambert

Taylor University: Charles Simeon

Eras of Elegance: Religion and Spirituality

The Regency World of Author Lesley-Anne McLeod

Jane Austen and the Evangelicals

A Nation Improving in Religion: Jane Austen’s Prayers and Their Place in Her Life and Art by Bruce Stovel

Nancy Mayer, Regency Researcher, The Bishops and Archbishops in England in 1815

Oxbridge Writers: George IV: The Prince Regent

Church Furnishing in 19th Century England

The History Guide: The Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England by Steven Kreis, Ph.D.

On Herschel’s Forty-Foot Telescope by Kathleen Lundeen

Amazing Grace: the Story of John Newton by Al Rogers

Jane Austen and Slavery by Ibn Warraq

Austen, Emma and the Prince by Stever King

From The Victorian Web:

Nineteenth-Century Riots and Civil Disorders

Victorian Science and Religion (referring to early 19th century beliefs)

Originally posted 2012-10-26 10:00:00.

Comments are closed.